How Your Brain Tells Stories: Visual vs Word-Based Imagination

Some writers and artists can't see pictures in their heads

Hello, lovelies!

When you read a book, do you (1) see the story play out in your head? Or do you (2) focus more on the characters’ emotions, with the visual parts of the story a bit faded out?

If you’re a writer, do you (1) imagine a story first as a movie in your head and then try to capture those images into words? Or (2) do the words come first, with the characters and the settings blooming from black-and-white type?

If you answered (1), then your thoughts, memories, and imagination work like most people’s.

But if you answered (2), then you’re like me. We have aphantasia.

I never knew I was different

Aphantasia is not a medical condition. It’s more like whether you’re right- or left-handed; in this case, it’s just how your brain works with images.1

When I was a kid, I never understood how the other preschoolers could draw such detailed, creative pictures, day after day. They told me that the ideas just showed up in their heads. But inside my head, it was just… blank. My drawings were always pretty basic; my best ones were derivatives of the other kids’.

I thought this meant I didn’t have an imagination.

We go through much of life assuming that everyone else’s brains work like our own, because we can’t get inside another person’s skull to experience how their thoughts work. This is how I came to a conclusion at a young age that I was not creative, because obviously everyone else was much better at Imagination (with an emphatic capital-I) than I was.

Fast forward four decades. I am now a New York Times bestselling author of eight novels, including a literary and film collaboration with Netflix. (Damsel spent two weeks last month as the #1 viewed Netflix movie worldwide.)

But how was any of this possible, if I had no imagination?

Visual vs Word-Based Storytelling

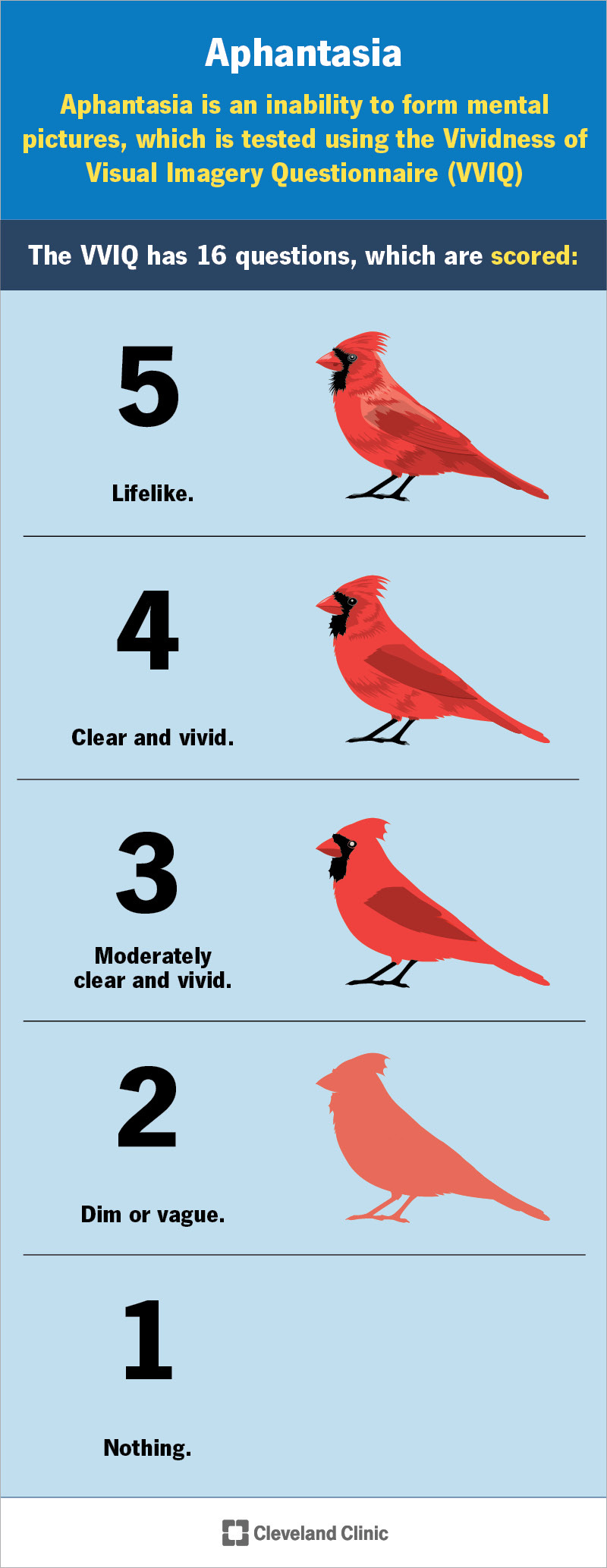

Aphantasia exists on a spectrum, and there is a medical test for it called the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ). However, if you were born with aphantasia, there’s likely no need to get tested2; the VVIQ is only for acquired aphantasia, like if you had a head injury and it suddenly changed the way you see (or don’t see) images in your head.3

Still, this scale is interesting, because everyone falls on it somewhere. For a fun, non-medical activity, you can take a look and see where you think you land on the phantasic-aphantasic scale:

3 - 5 means you are not an aphantasic. On the far end of the scale, 5s see thoughts/images in their brains with crystal-clear, lifelike clarity, as if that red bird you’re imagining were actually standing right in front of you.

1 -2 means you are an aphantasic. 1s do not see any images in their mind’s eye. 2s “see” images in their heads that are dim or vague. Only two to four percent4 of the population are aphantasics (also called aphants). Welcome to the club!

Again, it’s important to emphasize that aphantasia is not a disability or disease; it’s just a way you visualize things. (Aphantasia may be a form of neurodiversity, but that’s still being studied.)

Professions for Aphantasics

Not surprisingly, a lot of people who have aphantasia end up in the fields of science or math, where “seeing” images in their heads is not as important.

But what about art? Can you still be an artist if you don’t have a visual imagination?

Absolutely!

Look at my career. I went from a kid who supposedly had no imagination to someone who makes up worlds and characters for a living. My novels have been published all around the globe and translated into sixteen languages.

So how do I do it?

I approach my art differently—my way. I usually begin with the feel of a story or character before I know anything about them. I don’t see them as images in my head; I can’t build out detailed scenery in my mind. But I can feel.

Other times, the words come to me first. Whereas others might see a movie reel in their heads, I hear, see, and feel the words. Sometimes I literally see the words dancing in my head, as if they are being typed out in front of me. (Paradoxically, although I have a hard time seeing images, words appear clearly in my head— black font on white). This is a form of “typographic visual” imagination.5 Words also come to me as a rhythm and a melody; I can feel their beat and flow in the center of my chest.

As I begin to write the words onto my computer, the sense of the story begins to take shape. Note the “reverse” order of actions from that of most writers—they imagine first, then translate into words. I see nothing (or very little) first, so I have to get words down before the characters or the scenery begins to emerge. Maybe this is why, when readers and writers have asked me about worldbuilding and settings, I’ve always answered that the physical details of a place don’t matter as much as the ambience, the way a place feels.

Believe it or not, I don’t even know what my characters’ faces look like. When I’m beginning a new manuscript, I’ll scribble down a few sketchy details—black hair, pert nose, green eyes. But I do that because readers have “trained” me; they love to talk about the way my characters look, to make fan art, to come up with dream movie casts. It’s because most of them—like 96-98% of the population—are phantasics.

But for me? It doesn’t matter what my characters look like. What I’m really doing when I create them is embodying their hearts and souls. I become them and try to understand what makes them tick, what they yearn for, what loves and losses have they suffered? How does that affect the choices they make? And how will this make the reader feel?

This works for other forms of art, too, like drawing or sculpture. It isn’t necessary to have a crisp, exact version of an image in your head in order to bring it to life, as demonstrated by Disney artist Glen Keane. Just like I layer on words to create my stories, molding the phrases until they paint a (blurry but beautiful) picture, so, too, can visual artists bring their drawings and statues to life with their pencil lines and their hands to feel the pieces come alive.

Heck, maybe this is how the Impressionist art movement began! I wish I could ask Monet if he had aphantasia, too.

Now, let’s go back to the questions I posed at the very beginning of this piece.

When you read a book, do you:

see the story play out in your head?

Or do you focus more on the characters’ emotions, with the visual parts of the story a bit faded out?

If you’re a writer, do you:

imagine a story first as a movie in your head and then try to capture those images into words?

Or do the words come first, with the characters and the settings blooming from black-and-white type?

There is no right or wrong, no better or worse answer. You’re just you, unique and amazing as you are.

Share your perspective in the Comments! I am so curious to know how other readers and writers see in their imaginations.

Exclusive Newsletter Gift: Want a Postcard from Paris from Me?

My lovely French publisher, Hugo et Cie, is flying me to France next week for a book tour, including a signing in Lyon (at Gibert Lyon) and the Paris Book Festival. I’d love to send you a postcard while I’m there!

If you’d like a postcard, make sure you’re subscribed to this newsletter:

Then fill out this super short form. (I will only use your address for the postcard; I would never sell your personal information!) - Signup form closes on April 8, 2024 at 11:59pm PDT.

Book Clubs = Friends!

There was recently a piece in Refinery29 about how book clubs combat loneliness. If you’re looking for some bookish friends, join the next hangout of the WORDPLAY Book Club for Writers and Curious Readers!

We had so much fun in the first meeting (video replay here). I hope you will be able to join us next time!

Left/right-handed analogy from The Cleveland Clinic.

If you suspect you have acquired aphantasia, please consult a licensed medical professional. This post is not medical advice.

Since this is still a relatively new concept and not yet studied in depth, these percentages are just estimates. Some researchers say it’s 2-5%, but more work needs to be done to get a better idea on the prevalence of aphantasia.

Ribot T (1897). L'évolution des idées générales (in French). Serge,. Nicolas, Impr. Corlet numérique). Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 143. ISBN 2-296-02334-7. OCLC 494261389. source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphantasia

I've been working on my WIP for over a year now, and never understood why I struggle so much with physical description or visualising a scene and why it was so easy for me to write dialogue and character motivation. Thank you for this post, Evelyn! It makes me feel seen.

This must be on lots of people's minds lately – I have a draft post all about how people's imaginations and how they visualise things can be so different!!! I also have aphantasia, and I'm an author and illustrator ... for me it just means that the way I create art isn't the same as those who can visualise things clearly (or at least clearer than I can) in their minds. Not bad or wrong either way, just different.