Writing the Perfect First Sentence, First Paragraph, and First Page

How to hook readers, literary agents, and editors from the very start of your manuscript or book

Hello, you brilliant, wonderful people!

This week’s topic is how to write the perfect first sentence—one that grabs the reader (or literary agent or editor) by the scruff of their neck and never lets go.

Oh my. That sounded a bit violent. Well, imagine something gentler. Anyway, the thing that every writer knows is that the first sentence has to be good. But how?

I like to break it up into First Sentence, First Paragraph, and First Page. Let’s take them one at a time, shall we? In this post, we’ll use the first page of Damsel as a case study and discuss it line-by-line.

1. The First Sentence

I’ll admit that I often write the first sentence of a book later, during revisions. There’s a lot riding on that first sentence, and sometimes you just don’t know what it ought to be until you’ve really gone through a draft or two of the whole story.

That said, these are my three favorite approaches to first sentences:

Bold statement that sets the tone for the story.

“It is the first day of November and so, today, someone will die.” — The Scorpio Races by Maggie Stiefvater

Pithy observation on humanity

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” — Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Strong voice that captures the essence of the rest of the book.

“We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck.” — Feed by M.T. Anderson

“Appollonia ‘Onny’ Diamante walked into fifth period biology with magic tucked into the back pocket of her jeans.” —Three Kisses, One Midnight by Roshani Chokshi, Evelyn Skye, and Sandhya Menon

You’ll notice that I didn’t list the typical things that other writers recommend, like starting in the middle of the action or describing the status quo. That’s all fine and good, but to me, the real way you hook someone with a first sentence is with voice or feeling or insight. That first sentence is a promise to the reader about how this story—your story—is going to be special.

Don’t forget to check out:

Most recent newsletter: How I Wrote Four Books in 365 Days

Next newsletter: Social Media for Writers.

2. The First Paragraph

Once you’ve hooked readers with that first sentence, you need to keep their attention. At the same time, you need to ground them in this new story you’re about to embark on. That’s why I’m not a fan of starting a book in the middle of, say, a chase scene. Because as a reader, I have no idea who the character is, where they’re running from and to, and what the stakes are for the chase. It’s hard to care when I’m not yet grounded in the world.

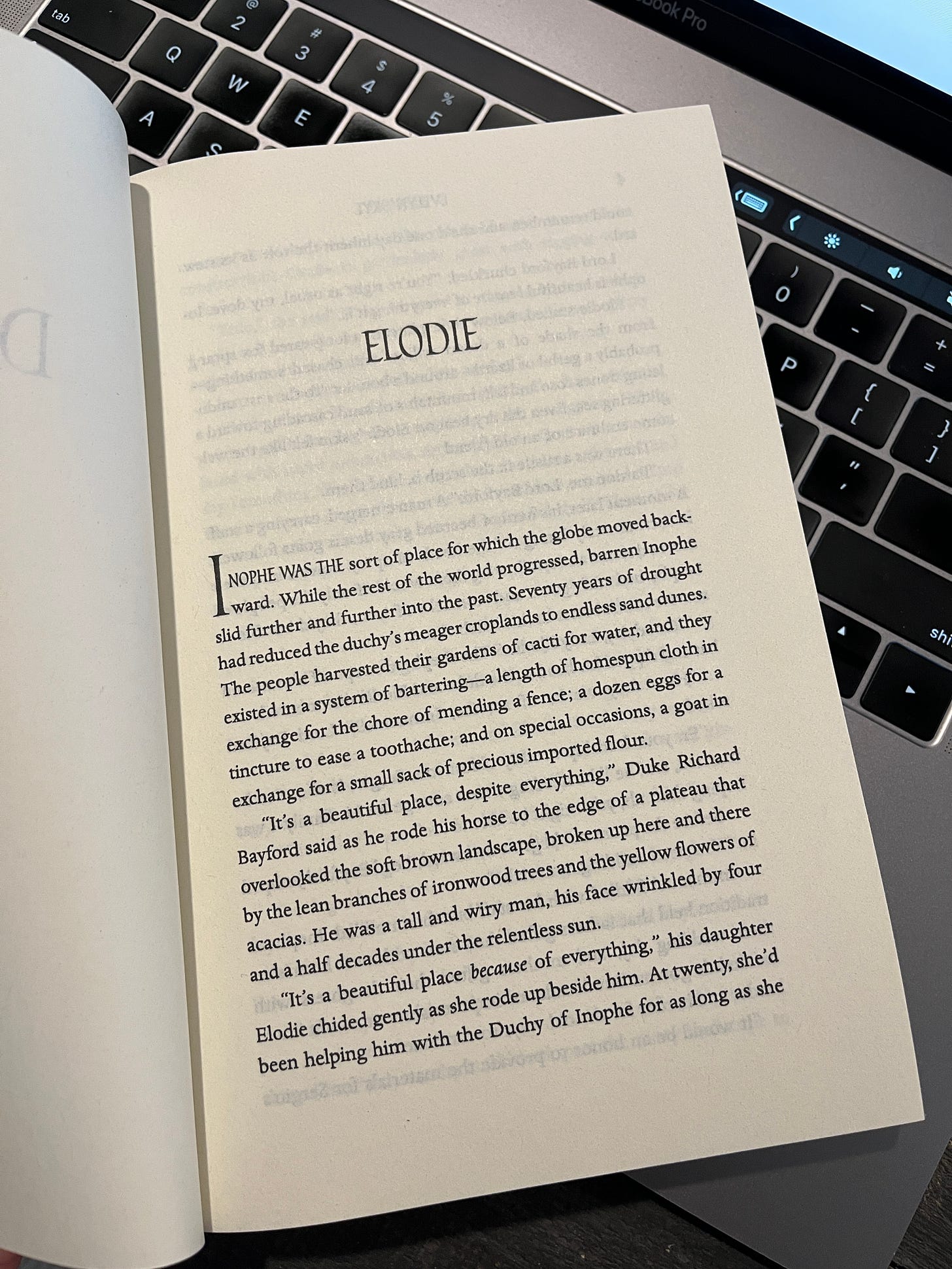

Let’s take the first paragraph of Damsel, my upcoming novel, and dissect it sentence-by-sentence.

Inophe was the sort of place for which the globe moved backward. While the rest of the world progressed, barren Inophe slid further and further into the past. Seventy years of drought had reduced the duchy’s meager croplands to endless sand dunes. The people harvested their gardens of cacti for water, and they existed in a system of bartering—a length of homespun cloth in exchange for the chore of mending a fence; a dozen eggs for a tincture to ease a toothache; and on special occasions, a goat in exchange for a small sack of precious imported flour.

“Inophe was the sort of place for which the globe moved backward.”

ok, this is a little weird to analyze my own writing and tell you why it’s good. So I’m going to pretend it’s not me, and I’ll try to point out what I think objectively works.

This first line sets the tone for the book—the observant narrator’s voice tells the reader that this story won’t just be a light romp, but there will also be some perspicacity about how people live.

“While the rest of the world progressed, barren Inophe slid further and further into the past.”

The second sentence supports the first, and clarifies what is meant by “for which the globe moved backward.” By describing Inophe in this way, the first two sentences also subtly set the reader up to expect the status quo to change very soon.

“Seventy years of drought had reduced the duchy’s meager croplands to endless sand dunes.”

With this sentence, the reader knows how to envision the place. It’s not a wooded country, or a tropical jungle. Inophe is a drought-parched, arid land. Packed into this sentence is also the information that Inophe was not always this way; in a few words, the history of the place is conveyed.

“The people harvested their gardens of cacti for water, and they existed in a system of bartering—a length of homespun cloth in exchange for the chore of mending a fence; a dozen eggs for a tincture to ease a toothache; and on special occasions, a goat in exchange for a small sack of precious imported flour.”

This last sentence of the first paragraph makes the setting personal. It populates this arid place with people and gives examples of their suffering. Now, the reader feels like they understand Inophe, and they are grounded in the story and its humanity.

3. The First Page

After the first paragraph has given readers a place to clearly imagine and feel, you need to introduce the main characters. Somehow, you have to show their personalities, establish them in the current state of things in their world, and continue to build the setting.

To do this, you want to weave character action and dialogue with character descriptions and more details of the scene.

Since we’re already looking at the first page of Damsel, let’s keep going with it:

“It’s a beautiful place, despite everything,” Duke Richard Bayford said as he rode his horse to the edge of a plateau that overlooked the soft brown landscape, broken up here and there by the lean branches of ironwood trees and the yellow flowers of acacias. He was a tall and wiry man, his face wrinkled by four and a half decades under the relentless sun.

“It’s a beautiful place because of everything,” his daughter Elodie chided gently as she rode up beside him. At twenty, she’d been helping him with the Duchy of Inophe for as long as she…

The second paragraph of the page introduces the reader to one of the characters, a middle-aged duke. I began with dialogue, because the first paragraph was all narration, and then added in action (he rides his horse) then layered in a few more details of the setting. This helps to flesh out the visuals of the world even more, without boring the reader (which is what would have happened if the second paragraph was just more scene description).

The duke’s dialogue serves as a smooth transition from the opening paragraph, because it’s a reference to the same setting the reader has just been “looking” at.

The third paragraph introduces our protagonist, Elodie. Her dialogue is an echo of her father’s, and yet it’s also a contrast. Just one different word illustrates how her perspective of Inophe is more buoyant than Duke Bayford’s. When she looks at this stricken land, she sees the beauty and strength in it, rather than what it lacks. In this way, the reader gets an immediate sense of her personality.

Also, the fact that she is riding with her father and can speak to him like this shows their affection and how he respects her, even though she’s only twenty. A couple of sentences can—and should—do a lot of heavy-lifting on the first page.

Ta da! A first page!

Keep in mind, this isn’t the only way to write a first sentence, first paragraph, and first page. But it does hit on a lot of important foundational principles, and I hope you found it helpful!